Fears of American Civil War Explain George Washington's Rise to Power

In the 1770s Washington was considered to be a bulwark against a New England civil war launched to dominate the Southern colonies

I promised you a cliff notes version of my book Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution.

Here is essay No. 2 from my 5-part series for the John Adams Institute. To find essay No. 1, entitled “The United States’ First Secession Threat,” click here.

According to more than two centuries of conventional history written about the grandeur and glory of George Washington of Virginia, the Continental Congress of 1775 “unanimously” elected him as commander-in-chief of the new American army for his celebrated qualities of moral steeliness, selflessness in the execution of civic duty, and courage under fire.

While this assessment of Washington, who had indeed proved his mettle in the preceding French and Indian War (1754-63), is historically accurate, it is an incomplete picture, a partial truth that overlooks two deeper life-and-death motivations for his promotion to the position of supreme military commander of the Continental Army.

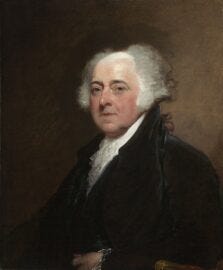

First, Washington hailed from the great colony of Virginia, which in the era of the American Revolution was the flagship of the Southern colonies. The leaders of the Congress wanted, as John Adams called it, a “Southern General” because they were desperate to unite the Southern colonies to the cause of the imperial war then taking place exclusively in New England. New Englanders, that is, wanted Southern help––and a show of American unity––in order to defeat the British after Lexington and Concord.

Second, and intimately connected to the first, many of the Middle and Southern colony delegates feared that a powerful New England army might make civil war on the other colonies if the Congress elected a New England commander-in-chief instead of a Southern one.

Many of the Middle and Southern colony delegates feared that a powerful New England army might make civil war on the other colonies if the Congress elected a New England commander-in-chief instead of a Southern one.

Thus, Washington was a bulwark against civil war, because it was confidently assumed that he would never stand by and watch the Continental Army turn its firepower upon Virginia and the other Southern colonies.

At the heart of it, my book Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution is about what the founders feared most in their political decision-making during the American Revolution. What I discovered in my research is that, more than anything, they feared civil wars among themselves. If they made gross political and military miscalculations––and certainly if they split apart into separate confederacies––they would kill one another on the battlefield.

Historians have long taught that the greatest threat to the new American states after the Revolutionary War was the British army and navy. But this is not true. The founders themselves believed that the greatest danger to the American experiment during these years was disunion and civil wars. Simply put, when it came to the politics of the American Revolution, the founders did what they did to save their souls from civil wars.

This crusade began in 1775 with calculated political decision-making designed to mitigate the risks of New England dominating the Continental Army and, far worse as a consequence, imposing its will by force of arms upon the other colonies. The evidence of these fears is robust. As John Adams made clear, the election of Washington was the product of “a Southern Party against a Northern and a jealousy against a New England Army under the Command of a New England General.”

In this evaluation, Adams was saying that the delegates in Congress feared the territorial imperialism of New England. To understand the reality of this possibility, we must remember that the founders lived in an age of imperialism. It was normal and expected that nations (including a new republic like New England) would expand and exploit their neighbors—if they could.

Here is the three-step chain reaction many delegates in the Congress feared in 1775: First, the formation of a New England army commanded by a New England general; second, that army would win the War of Independence against England; and, third, with its blood still pumping hard from victory, the New England army would militarily exploit and possibly conquer the other American colonies.

The founders did what they did to save their souls from civil wars. No governing political principle better explains their decision-making during the Revolution, including the election of Washington as commander-in-chief, than this one.

John Adams is not the only delegate who left behind evidence documenting this overriding preoccupation of the founders. Another New Englander, Eliphalet Dyer from Connecticut, fifty-three years old and like Washington a former officer in the French and Indian War, made the same argument in a letter to Joseph Trumbull, Connecticut commissary general.

“It removes all jealousies,” Dyer wrote, and “more firmly cements the Southern to the Northern, and takes away the fear of the former lest an enterprising eastern New England General proving successful, might with his victorious army give law to the Southern & Western Gentry.” In a second letter, this one to his home colony’s governor, Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., Dyer affirmed, “His appointment will tend to keep up the Union & more strongly cement the Southern with the Northern colonies, & serve to the removing all jealousies [an] army composed principally of New Englanders (if happily they prove successful) of being formidable to the Southern Colonies.”

It is not surprising that fear of internecine death actuated the founders in their every political move in the 1770s and 1780s. After all, they knew they must remain united, instead of disbanding into separate confederations, in order both to prevent civil wars among themselves and to win the War of Independence.

The founders did what they did to save their souls from civil wars. No governing political principle better explains their decision-making during the Revolution, including the election of Washington as commander-in-chief, than this one.

Eli

This post is most interesting and somewhat reminds me of what is and isn’t happening in the House of Representatives now.

Hi Sheila! You are right. Hope to see you soon. Best,